Speaking of illustration:

A transcript (ish) of my interview for Speakers4Schools this week, covering copyright, life as an illustrator, the myth of creativity…and AI.

This is a long read. Get the kettle on, and maybe some biscuits!

— — — — — — — — — // — — — — — — — — —

This week I gave a talk via the Speakers For Schools programme to a large, digitally-assembled audience of schoolchildren from schools around the UK.

Live from my studio I was invited to answer questions posed by host Charlotte, followed by questions sent in by the students as they listened. This is always my favourite bit — the questions an audience asks, particularly one composed mainly of children, are always the most interesting to answer, for they are often surprising, insightful, cheeky, direct, oblique or all of those things at once.

I’ve missed travelling to events, schools and universities over the last year, environments in which I’d be chatting on a stage to potentially hundreds of listeners, but it’s actually been very freeing not to have to organise the logistics of a long drive or a train trip — and I’ve not missed the amusingly awkward fifteen minutes it usually takes to get my drive, disk or CD talking to a college PC system!

No; instead, I’ve been able to prepare, present and chat from my own studio, which means longer talks, and more relaxed environments for all.

I made notes for this most recent talk as I usually do, because although I never read notes verbatim, especially in a stage situation, I wanted to stay on track and not waste any time fumbling for answers. Since I typed them all out though, I thought it would be useful to share those answers together with the questions here, as they’re things I get asked a lot.

I’ve added a couple of my favourite ‘Q&A’ questions from the end of the session.

I hope they’re useful! Keep in mind that any one of these questions could be expanded into at least an hour-long talk all by itself, so these are skimming the surface; this part of the talk was only 40 minutes long. All the images are from the slideshow.

If you’re interested in organising a talk for your own college, school, event or university, do get in touch.

— — — — — — — — — // — — — — — — — — — -

Firstly, please can you tell me how ‘Inkymole’ came about?

When the time came to set up my first ever website, sarahcoleman.com was already taken, and there were far fewer domain options in those days. At school one of my nicknames was Mole, both because of chronic short-sightedness and because it rhymed with Cole (another nickname) and Colehole (yet another), and because I was always dabbling about with ink and paint, the ‘inky’ part began to stick too.

So the obvious choice for a domain, which was only ever meant to be a temporary solution, was inkymole.com. It wasn’t long before people started ringing up and calling me Inky, or asking for Inkymole — and so it stayed!

(and sarahcoleman.com STILL isn’t available — it’s owned by a company who buy up domains purely to sell to the highest bidder — a practice I don’t approve of.)

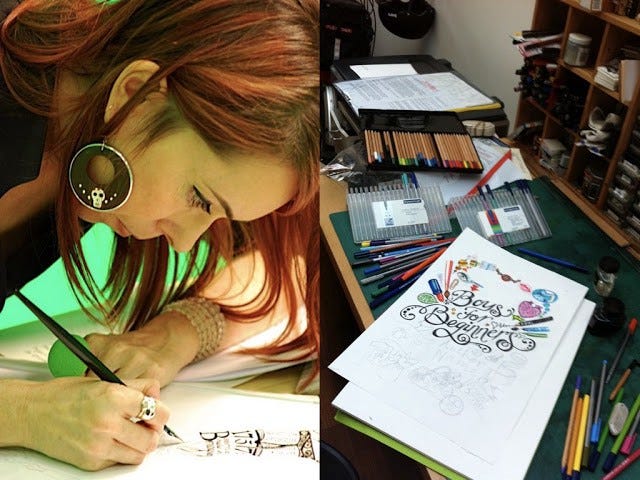

Please could you talk to us about what is it like to work as an illustrator and some of your responsibilities?

- Hard work. It’s always hard work!

- You may work by yourself — at home or in a studio — but you’re part of a team whose job it is to get work completed and often to print to a deadline.

- You need to be able to get the job done on time, on your own.

What are some of the skills you need to be a successful illustrator?

- Flexibility and adaptability — both in terms of your ability to manage time, when you can / want / need to work, and in terms of your style and way of working.

- Perseverance and the ability to stand your ground; this’ll be important in negotiating contracts and fees, and in arguing your corner when you feel a direction isn’t right, or something won’t work a particular way.

- Must be able to take feedback and criticism objectively — it’s not personal.

- You need a flair for marketing and self-promotion without sounding fake or inauthentic. If it’s just you say YOU! (If there’s no actual ‘we’, never use it.) Also: people KNOW when you’re being sales-y vs. just talking ‘in your own voice’.

- Ability to manage cashflow!

Please can you tell us about some projects that you have worked on that have been really memorable and why?

There are loads, from very small projects to very large ones, and not all for clients. Here are some; they’re all on my website (apart from the one marked with a †).

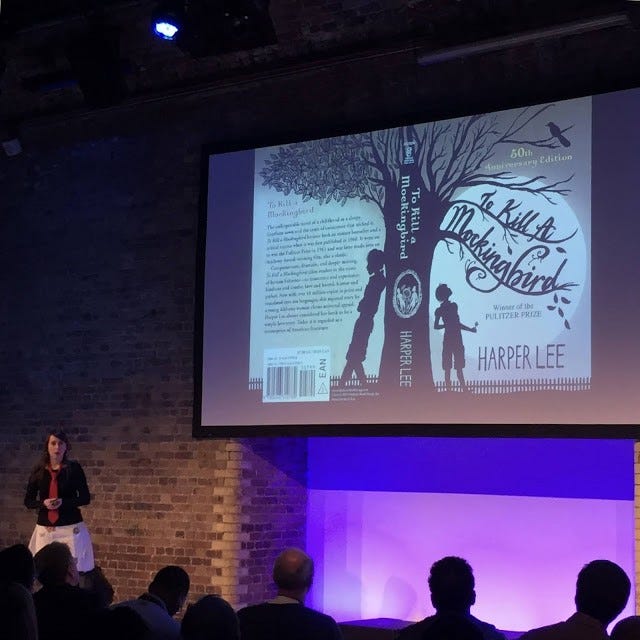

- My 50th anniversary ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ cover.

- Illustrating ‘Out To Get You’ and ‘Only If You Dare’† by Josh Allen.

- Some of my own shows; big logistical and creative personal challenges.

- The Playboy cover!

- Hillary Clinton’s book cover.

- The 72ft billboard in Times Square.

- My July 4th Fireworks poster for Macy’s.

What are some of the main challenges of being an illustrator?

- Staying in work — generating enough to make a living, long-term and consistently — and not only ‘a living’, but the kind of living you want, whether for you that means ‘I want a big house’ or ‘I need to be able to support loads of kids’, ‘buy a horse’, ‘have four holidays a year’ or ‘I’m happy with enough to cover my bills’.

- Managing jobs and your time (you’ll often have more than one job to do at once, often for overlapping deadlines).

- Staying on people’s radars; it’s a very competitive trade.

What advice do you have for aspiring young illustrators?

- Start looking for clients and work (experience) BEFORE you leave education. When you leave, you’ll be swimming upstream with thousands of others, all trying to get work. This means making contacts, doing interviews with people in industry, writing to them, maybe working for them (work experience), inviting them to your end-of-course shows, and more.

- Your best work is yet to come, so don’t worry about how your work looks right now — it will change throughout your life, and it should.

- Never put work in your folio that you don’t actually like or didn’t like doing — even if it’s brilliant or been published or you got paid a lot for it. If you hated doing it and don’t want to work like that again, don’t show it to anyone; that way lies madness.

Are there any misconceptions about illustration and what would you say to address them?

- It’s not just about kids’ books!

- Yes I do kids’ books.

- That ‘it’s easy’ — I have DEFINITELY got the impression people think my job is easy!

- That we’re willing to knock out a drawing in front of the TV. If we’re watching TV, we’re watching TV, not working (and vice versa)…

…ergo, just because it’s art and we use crayons doesn’t mean we’re going to do it for free.

How has technology advanced throughout your career and do you think it has created more opportunities for illustrators?

- It’s made it easier than ever to show work publicly, and deliver it worldwide, cheaper than ever (free in a lot of cases).

-Technology has sped up the process of actually making [some types of] work and delivering it — I’m thinking of the obvious software, Apple Pencils, and the internet at large — but it hasn’t sped up the process of learning to create illustration, think up concepts, answer briefs. And it definitely can’t speed up or create shortcuts for gaining experience.

- However, technology means that your competitors are ALSO visible, and suddenly you realise there are thousands of you, any of whom can do the job — whereas when I started, you were mainly hired by clients in the same country, and your work would only be seen if you sent it specifically to the client or they’d seen something you’d had published.

- This also means you were mostly only aware of illustrators who’d been published, rather than the situation we have now where anyone can share any of their work 24 hours a day, published or not, professional or amateur alike — and we can all see it (and see how good it is!)

In other words: technology means that illustrators trying to gain a foothold in the business today are competing in an enormous, omnipresent market — clients are spoilt for choice.

What inspires you to be creative?

- Every human is creative, we all just express it and use it in different ways. I’m no more or less creative than a plumber who solves a particularly difficult piping problem, a café owner who’s found a way to carry on retailing through the lockdowns, or a coder who can’t work out a game problem!

- So I wouldn’t say I have to ‘become inspired’ to be creative; I just am — as is everyone, in their own way.

It’s just that I ‘look’ more creative because my work is visual, and can thus be ’seen’ — being ‘able to draw’ has long been seen as a benchmark of being creative, but I don’t think this is accurate.

- On a pragmatic note, I’m paid professional-level fees because of my ability to create on-demand — so I can’t really ‘wait for inspiration to strike’ if I have a deadline.

[Having said that — see below!]

What do you do if you are having a bit of a creative block?

- I go back to the book/brief and have another look!

- Ask the art director for more info/a chat.

- If the deadline allows: switch to a different job for a bit.

- If the deadline doesn’t allow: send what I have! You never know, the client might like it anyway (the best advice an agent ever gave me).

- Sometimes it helps to get the obvious solutions or clichés out of the way — just do them, work through them, maybe send them; at the very least look at them, because that often leads to a clearer path to something more interesting.

- If none of that works: give up! Go back to it later (again — if deadline allows — if not — you have to plough on — it’s what you’re paid to do!) And do something else.

As stated in the last answer, as a professional you’re paid money to create to order so, although creative block does occur (you’re not a machine), as a pro, you need to have the strategies to get past it and deliver the work — even if you don’t think it’s your finest output!

~ My two favourite Student Questions ~

Have you ever had to deal with copying, infringement or plagiarism?

I have. Many times. But I need to break my answer into two parts; first, being copied or imitated.

A few years ago I was getting messages from chums and even family saying they liked the work I’d done for a particular high street store (there’s a little crew of people who go Sarah-Spotting). It had been a VERY busy few months so I looked up the work they were talking about as I couldn’t remember doing it; this didn’t mean I hadn’t, it’s just that sometimes the lead time between doing a job and the job going live is quite long — as much as a year and a half sometimes. And as I said…it HAD been a really busy time.

However, this one I had NOT done — but for second I thought I was losing my mind as it just WAS my work. I looked EXACTLY like I’d done it. The rest of the story is here, but I realised that yes, my style, energy, the movement in my work, the way things flowed across a space, and the other intangible, slightly hard to articulate things that make my work ‘mine’ had very definitely been mimicked — almost studied. The artist in question maybe knew, or maybe didn’t know, just how similar their work was — either way, they carried on working in that way for a good long time, and I had to really keep an eye on things for a while there.

Mimicking a style is harder to prove, should a court situation ever arise, and indeed a recent case of one lettering artist vs another lettering artist which almost came to blows in a very public way was a good example.

The second thing I’ve had to deal with is infringement. (This is distinct from plagiarism — which is a specific piece of work being copied and passed off as an original:

‘Plagiarism and copyright infringement overlap to a considerable extent, but they are not equivalent concepts’ — Wikipedia.) I’ll often share examples on my Instagram account partly to let current or potential infringers see that what they’re doing is easily discovered.

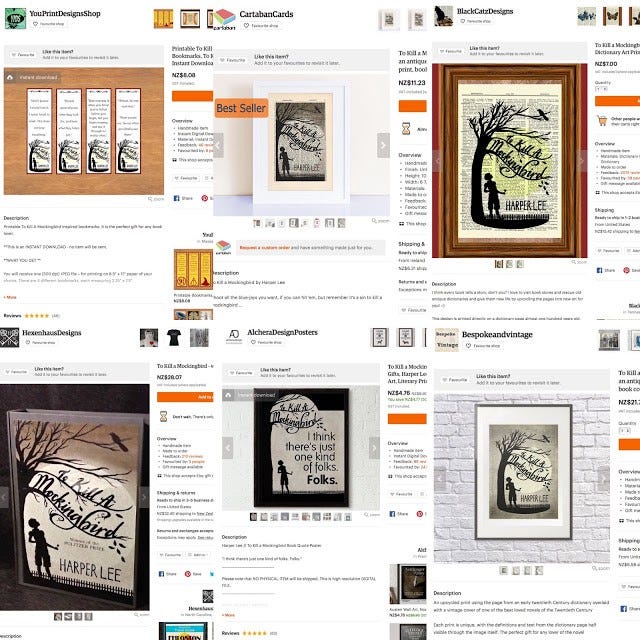

My work has been stolen constantly by users of Etsy and Redbubble for making their own (mostly terribly-put-together) products. I have to report each case and get the listing — or in extreme cases, the account — taken down. I bet that if I went to Redbubble or Etsy right this minute, I’d find a new one!

[Note: I did.]

[Secondary note: I found 7.]

A full blog on this subject is due for publication soon.

What do you see as the future for art and illustration in relation to technology and AI?

This was a big question that I didn’t see coming. But my reply was an honest one. Since this wasn’t written down, this is a rough transcript of how I answered! (expanded on a bit).

Although AI and technology in general has made breathtaking leaps in my lifetime — from the very hyperlink itself to synthesising art and the creation process, piercing together visual information fed to neural networks to make ‘new’ things, AI-generated music like that of Holly Herndon’s ‘Spawn’, and robots which are getting closer to mimicking the natural movements of humans, such as everything Boston Dynamics has been working on, I feel sure that the kernel of that which makes art and ideas — the human mind — cannot be replicated in its full form. Not only that, it’s the human mind (rather than merely ‘the brain’) working in conjunction with the intricacies of human decision making, moral, aesthetic and emotional judgements, feeling and intuition, nuance and storytelling, and solving problems presented by human existence, which complete the recipe for creating things.

We will probably one day soon see a walking, talking robot that mimics us and can hold a pencil or paint on canvas or write soliloquies in seconds, but it will still be a machine. (I recommend reading Ian McEwan’s ‘Machines Like Me’ which explores this in detail.)

And that makes me think that if that happens, the market may divide into a situation similar to that seen in wartime, when you had, for example, ‘real’ coffee and ‘ersatz’ coffee, or flour made from acorns; the crap stuff, but it was passable when the real deal was unobtainable or unaffordable. At ground level, as opposed to within the research labs or billionaire’s basements, there’ll be Machine-Made Art (MMA) which is cheap and plentiful and just about adequate, and there’ll be Human-Made Art (HMA), which is the real thing, and comes at the appropriate price. Like the difference between a mass-produced made-in-China thing or one hand-made by a craftsman in a workshop. (There may be a lifelong love of the film Bladerunner with its replicants coming through there). And

We’re seeing the beginnings of something which feels a bit like that now with the likes of Fiverr, where you can get a logo banged out for literally a fiver, which will ‘do the job’; but if you want something properly considered, unique, designed and refined, you go to a trained, experienced professional. There’s an argument there that the Fiverr model is the democratisation of design — that you don’t need a degree or training, merely the right software and an ambivalence about the outcome — and that these £5 logos are just as good (indeed some of the people on Fiverr claim to have many years of experience). But that’s for another blog entirely!

Ironically art made with machines (digital) is now being sold by machines as NFTs for ‘I really need to sit down’ sums of machine-generated money — forcing all of us to think about what ownership means — both taking ownership of something’s creation in the first place, and ownership of a finished piece — and whether, when provenance of digital work is as traceable and provable (maybe more so) than physical pieces, there remains any value in the concept of one-offs and originals.

So my outlook is optimistic, while remaining realistic. Those machines are not getting any less clever.

— — — — — — — — — // — — — — — — — — — -

Thank you to Charlotte Stringfellow and Lily Clifford at Speakers4Schools for organising, hosting and editing the talk.